Solutions

When the climate story is told only through the lens of carbon, it can feel impossible to make a difference. The problems seem too vast, the solutions too technical, and the power to change things out of reach for most of us.

But restoring the water cycle is different. It’s local. It begins right where we live, in gardens, streets, parks, fields, and forests. And almost anyone can help.

Help Water Soak In

Bring Back the Green

Help Water Soak In

In many places today, rain is treated as a problem – something to get rid of. But every drop that runs off is a drop lost from the land.

Instead of sending it away, we can help water stay – and slowly soak into the ground, where it feeds the soil, the plants and even the air.

It’s all about slowing the water down and spreading it out, so it can infiltrate and replenish the water table.

In your Garden

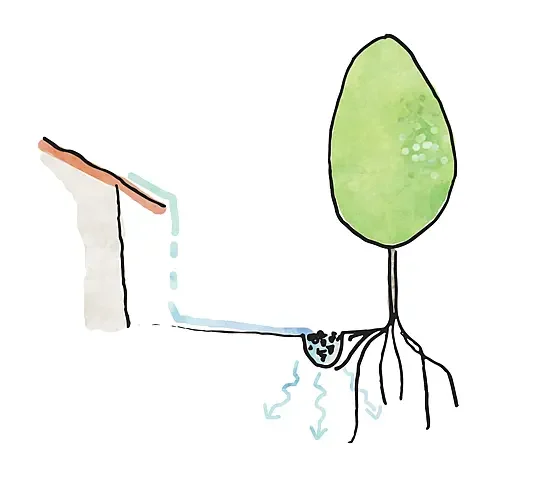

Try to infiltrate all the rain that falls in your garden and on your roof into the ground, so that it isn’t lost by running off into the street or down the drain. Next to capturing the valuable rain, this also reduces the amount of watering you have to do. You can collect rainwater in a tank to water your garden or you can direct gutter downpipes into infiltration trenches or rain gardens.

Detailed info on the following water infiltration techniques can be found in the books by Brad Lancaster. See our resources page for more information on his work.

Infiltration Trenches

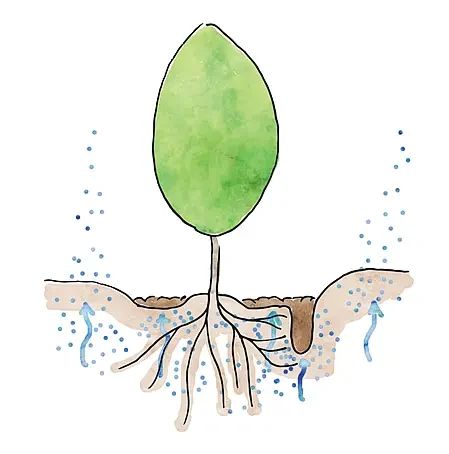

An infiltration trench is a trench or basin filled with porous material like gravel, pumice stone or rough organic matter that has lots of airspaces so that water can quickly infiltrate and soak into the rootzone of the surrounding soil. They can be used on flat and gently sloping land, and work well for catching runoff from roofs or a paved patio, because this water will not have a lot of sediment and not clog up the trench very fast.

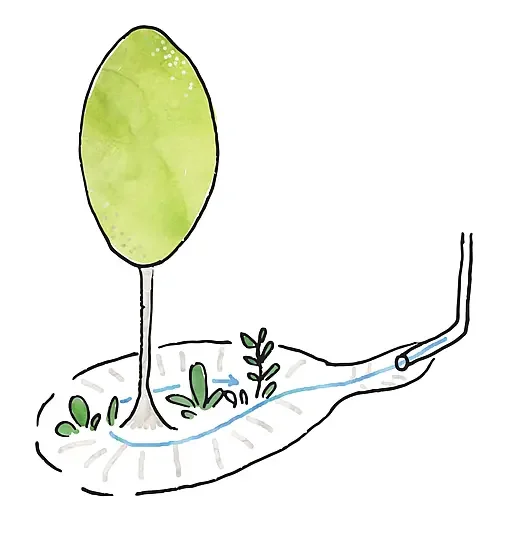

Rain Gardens

A rain garden is not filled with gravel. It’s a shallow basin that catches and soaks in rainfall and creates an ideal area for planting. These infiltration basins should avoid creating pools of standing water, to avoid breeding of mosquitos.

Mulching

Mulching can be added to these basins; it creates a thick layer of spongy organic matter that helps catch, hold and infiltrate rain. Without mulch, these basins quickly lose moisture to evaporation — but with a thick organic layer, the water stays in the soil where plants can use it.

Deeper holes filled with mulch within rain gardens can be created to help water infiltrate even deeper in the root zone. Mulching is a great strategy in general for many other areas of your garden; it helps keep water in the soil so it can be used by vegetation and trees, and it improves your soil by adding organic matter and protecting valuable life like earthworms and fungal networks.

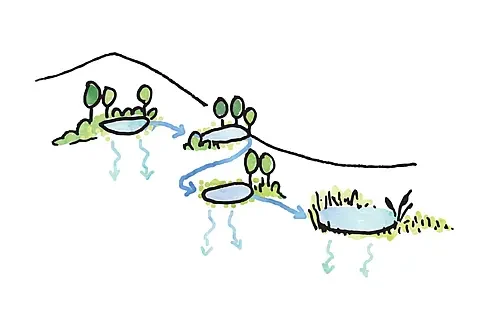

Diversion Swales

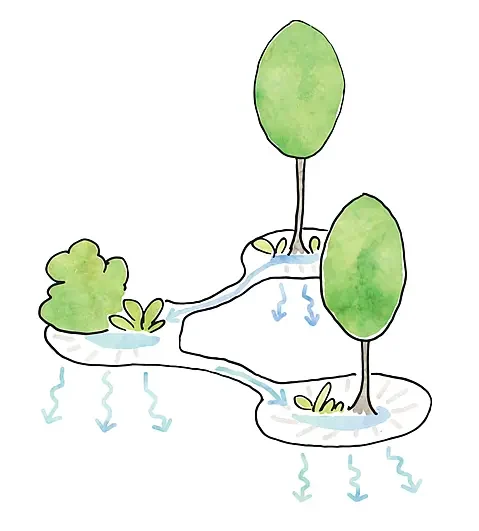

Diversion swales can be used to slowly and calmly move water from one part of your garden to the next. They are shallow drainageways that are created just off-contour to make sure there is only slow and calm movement of water, and they can connect several rain gardens to help you spread the rainfall throughout your property.

With any water infiltration features it’s important to stay at least 3 m away from the foundation of buildings.

In Cities

In cities a large volume of water is captured by roofs of buildings and by paved areas, but most of this is discharged into the sewage system, There it mixes with black water, greatly increasing the volume that needs to be treated by the city’s water system. City trees are often struggling because they are planted in areas that are almost completely sealed off and paved over, with minimal rain being able to get into the soil.

Instead of letting it run into the sewers, this valuable rainwater can be soaked into the ground where it falls to support plantings and trees that create natural and free air-conditioning and cool shade, making the local city climate much more pleasant. Infiltration trenches, diversion swales and mulched rain gardens can also be used in cities, in between apartment blocks, along streets, and in parks. Runoff along streets can be diverted into planted areas by “cutting the curb”, creating green cool oases in the city.

In the landscape

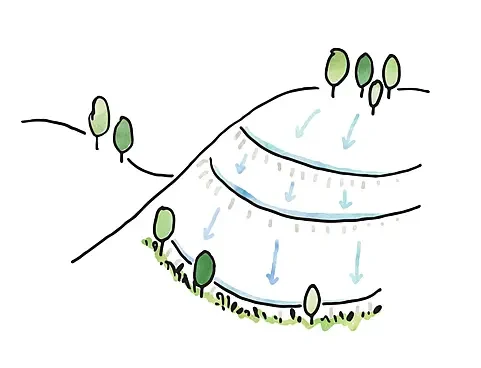

Every action that slows water down and gives it time to soak in in the wider landscape helps rebuild the water sponge –the local water table and the small water cycle. Many of these techniques are not new — they’ve been used for centuries in traditional farming cultures around the world. What’s new is the understanding of why they work so well — and how helpful they are for restoring the water cycle today.

With these techniques, you create a net of water catching features that makes a landscape a sink instead of a drain.

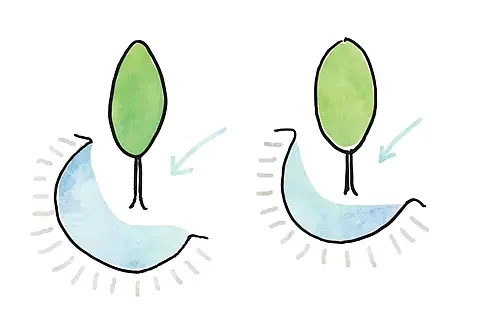

Berm & Basin

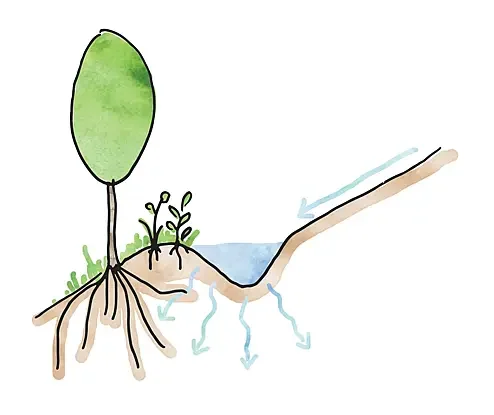

A Berm and Basin is a simple earthwork built on gentle slopes to catch rainwater and help it soak into the ground. A shallow trench (the basin) is dug along the contour line, meaning it’s placed where the ground is level from side to side, so that water spreads out evenly instead of rushing downhill.

On the downhill side of the trench, a small berm is built using the soil, rocks, or brushwood from the excavation. This low mound helps hold the water in place, giving it time to infiltrate slowly into the soil.

These wetter zones support the growth of grasses, shrubs, or trees that help stabilize the slope, protect the soil, and create mulch and organic matter. It makes the whole system even more effective over time.

Berm and Basin systems can also be shaped in boomerang curves around young trees or shrubs, to help them establish strong roots in dry or degraded landscapes.

Sheet Flow Spreaders

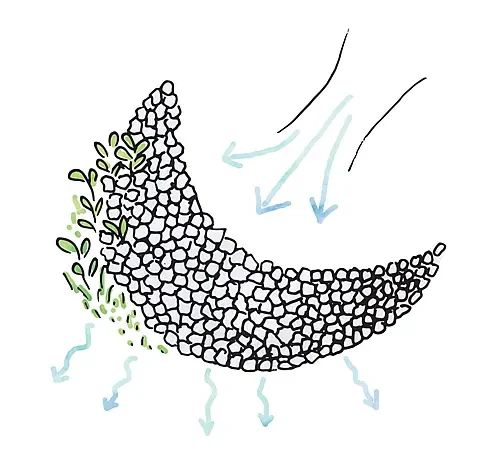

In areas where water moves quickly across the surface, carving small channels and causing erosion, Sheet Flow Spreaders help slow it down and spread it out.

They’re usually made by placing rocks in gentle, curved lines (like half-moons) across the flow path. These barriers catch sediment carried by the water and allow it to settle, slowly rebuilding the soil.

As the soil improves, it can hold more water — and plants begin to return. Over time, these simple stone curves turn a damaging flow into a gentle force for rehydration and regeneration.

One-rock Dam

A one-rock dam is a low, leaky barrier built across small gullies or erosion channels. It’s just one rock tall but wide enough to hold back water and slow its flow.

By spreading water out and letting it pool briefly, it gives moisture time to soak into the ground. Sediment settles behind the dam, gradually rebuilding the channel bed and making space for plants to return.

These small structures help reduce erosion, retain soil and moisture, and begin healing eroded land, one rain at a time.

Seasonal Stream Barriers

These can be created across seasonal streams or drainage channels that only flow after rainfall. They are low, leaky dams made from natural materials like logs, stones, brush, or earth, and are designed to slow the flow of water, giving it time to infiltrate into the ground instead of rushing away.

If water begins to erode the area just below the barrier, you can stabilize it easily by laying down rocks to protect the soil and slow the drop.

As the flow slows and pools behind the barrier, it starts to recharge the water table, support vegetation, and reduce erosion.

Important: These barriers should not be placed in streams that flow for most of the year, as they can block the movement of fish and other aquatic life.

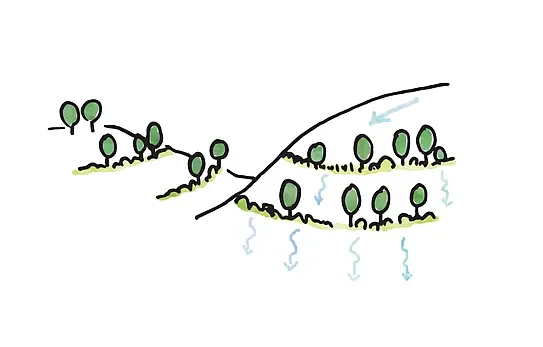

Vegetation along Contour Lines

Strips of grasses, shrubs, or trees can be planted or allowed to grow along the contour lines of a slope. They become soft, living barriers that slow down water, catch eroding soil, and help moisture soak in.

By reducing runoff and wind, they protect nearby crops and over time they become the lost hedgerows and field boundaries that used to help with water infiltration in the past.

Small Ponds & Water-Holding Features

When connected with diversion swales, a series of small ponds can form a network that gently guides water through the land, instead of letting it rush away.

Ponds recharge groundwater, support birds, frogs, and wetland plants, and help buffer the land against both floods and droughts. The wetland vegetation that grows around them helps release water vapor into the air and supports the small water cycle.

From Flowing Life to Static Lake

What Happens When a River Becomes a Reservoir

You might think that building big reservoirs is a perfect solution: more stored drinking water, flood control, even a huge new lake. But the reality is more complicated…

Natural rivers don’t just carry water — they shape entire landscapes. Along their winding paths, they create a rich mosaic of wet habitats: seasonal floodplains, wet meadows, riparian forests, oxbow lakes, and marshes. These areas are dynamic and diverse, supporting a wide variety of species, maintaining high biodiversity, and helping to regulate water and the local climate.

But when a large dam is built, and a reservoir is created:

- The upstream landscape floods — but instead of recreating those varied wet habitats, it becomes one deep, static body of water.

- Shallow floodplains disappear, replaced by steep, artificial shorelines with less ecological value.

- Wetlands that relied on regular seasonal flooding often dry out or are permanently submerged.

- Downstream flow is regulated by humans, often reduced to a trickle most of the year, punctuated by unnatural pulses of discharge that can cause erosion or flooding without restoring the wet habitats.

So instead of a long river corridor with hundreds of kilometers of biodiverse, wet-rich ecosystems, we end up with:

- One big, deep reservoir with far less edge habitat

- Far fewer shallow zones and wetland conditions

- A disrupted system that no longer breathes with the seasons

This means that, paradoxically, although there’s a lot of water in a reservoir, there’s often less wet habitat overall. And this loss has knock-on effects for birds, amphibians, mammals insects and plants — as well as for water retention and cooling in the landscape.

See our resources page for more information on what you can do to help water infiltrate

Bring back the Green

Planting Trees

Planting and caring for trees may seem like a small act, but it’s one of the most effective things we can do. Trees cool the ground, hold water in the soil, and …and play a role in supporting local rainfall patterns.

Protect the Trees we already have

They’re already doing the work of cooling the air, anchoring the soil, and bringing water back into the cycle and it can take decades for a young tree to grow into that role.

Here’s how we can help them thrive:

- Add mulch around the base of the tree to keep the soil moist, protect against evaporation, and nourish the soil as it breaks down.

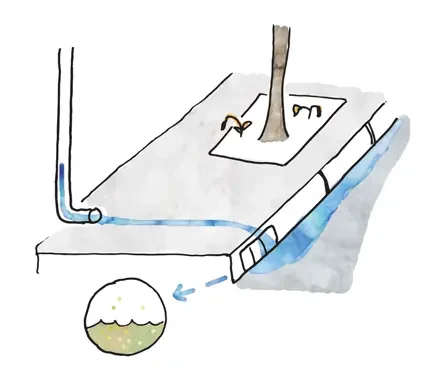

- Divert rainwater — from roofs, paths, or compacted areas — so it gently flows toward the tree’s root zone instead of running away.

- Protect the roots by avoiding paving, parking, or digging too close to the trunk. Tree roots often grow close to the surface and can be damaged by heavy digging. Instead, gently loosen compacted soil with a garden fork or make small infiltration holes to help both water and air reach the root zone.

Plant new Trees

In gardens, neighborhoods, parks, fields, or schoolyards — planting a tree is a quietly powerful act.

Each new tree helps cool the ground with its shade, and becomes a natural air-conditioning unit — making the local climate more pleasant, especially in the heat of summer.

But trees offer more than just water and shade. They help people feel better, too. Studies show that time spent near trees can reduce stress, improve mood, and even speed up healing in hospitals. Greener neighborhoods tend to have lower crime rates, more community connection, and better air quality — because trees filter pollutants and release natural compounds that can calm the nervous system and support overall well-being.

Each year gorata.bg is giving away thousands of trees to anyone who wants to plant them and care for them. Keep an eye on their notifications here to find out when trees are gifted near you:

Gorata.bg website

Gorata.bg Facebook page

Help Young Trees Survive

Help Young Trees Survive

Planting is just the beginning, a young tree needs care in its first few years, especially during dry summers when its roots are still shallow. Here’s how you can help:

- Mulch generously around the base of the tree (but not against the trunk). A thick layer of organic mulch — like leaves, wood chips, or straw — keeps the soil cool, holds in moisture, reduces weeds, and slowly feeds the soil as it breaks down.

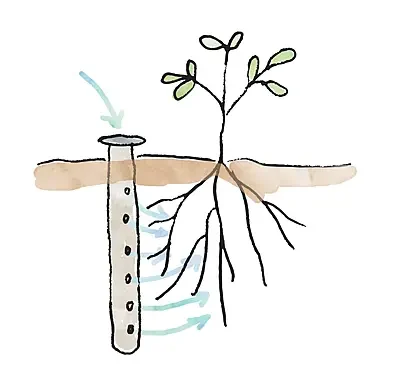

- Water deeply, not often. Instead of shallow surface watering, you can plant the tree with a buried perforated pipe to water deeper in the root zone where it matters most. This encourages roots to grow downwards toward long-term moisture.

- Wick watering is a low-tech solution to help watering young trees if you are not available to water it for a while. You can use a big water bottle or other container, and lead a cotton or nylon rope through a clear plastic tube, and then into the ground near the tree to slowly wick moisture into the soil.

- When possible, capture rainwater from nearby roofs, paths, or other hard surfaces and guide it to the tree’s root zone. A small diversion or trench can turn runoff into a gift — helping the tree make the most of every drop.

Without this support, many young trees don’t make it past the first dry season.

Plant the Right Trees

Whenever possible, choose native or local trees that thrive in your climate and support the local ecosystem. In cities, choose trees that provide shade, beauty, and resilience — and help restore the small water cycle.

Let Nature Do the Work

In some places, all you need to do is stop mowing, grazing, or disturbing the land.

If there’s enough moisture, trees and shrubs will begin to return on their own — the land remembers how to grow green.

Letting this happen, even in a small corner of your land, can be just as powerful as planting.

Tiny Forests

A Powerful Way to quickly create woodland

Mature, Multilayered forests

Woodland and forest cover is important for building climate resilience. Trees help moderate local temperatures, slow down floods, stabilize soils, release condensation nuclei that help clouds and rain form, and keep moisture in the ground by creating shade and spongy soils.

But not all forests are equal in how well they perform these functions.

Mature, multi-layered, native forests are the true champions.

They have deep root systems, long-established fungal networks, and a rich mix of plants, birds, insects, and mammals — all of which help create a stable, thriving ecosystem.

Ancient Natural Woodlands

Ancient, natural woods are even more important. When woods are logged and managed by man, old dying trees are removed or not allowed to grow old at all and harvested instead. But standing, dying trees, fallen logs, rotting stumps and fallen branches are the richest habitats in a healthy forest that create a home for many of our rarest woodland species.

Protecting the last of these natural forests is incredibly important. They take decades or even centuries to form, and once gone, they are nearly impossible to replace in full.

They also act as living reservoirs of biodiversity — sheltering species and fungi that can re-colonize or be reintroduced into nearby restored areas. Without them, the web of life we hope to rebuild has nowhere to return from.

Because mature healthy forests take decades — even centuries — to reach their full richness, it can make starting new forests feel slow or out of reach.

But what if there was a way to accelerate nature’s timeline — and grow a thriving, layered forest in just a few years?

That’s the promise of the Miyawaki Method and the Tiny forest movement.

Creating Tiny Forest won’t be able to replace our ancient mature forests, but they can help us establish more mature woodland fast.

What Is a Tiny Forest?

The Tiny forest method was developed by Japanese botanist Dr. Akira Miyawaki and creates tiny, ultra-dense native forests that grow up to 10 times faster than normal woodlands — reaching maturity in just 20–30 years instead of 200.

You only need small spaces; 100m2 is enough, roughly the size of six parking spaces. They are especially powerful in cities and villages, where small, unused plots can be transformed into cool, green, rain-supporting oases.

These small but mighty forests use:

- Only native species, selected for local soil and climate

- Multiple layers (shrub, sub-tree, tree, and canopy)

- 3–5 plants per square meter — creating competition and rapid growth

- Special soil preparation with compost and beneficial fungi (mycorrhizae)

- No chemicals or fertilizers

- Little to no maintenance after the first 2–3 years

Tiny forests are thriving in places as different as Paris, Jordan, and the USA — bringing shade, life, and resilience back all around the world. They’re also succeeding in tough climates. In dry Mediterranean regions, where most tree-planting struggles, Miyawaki forests also established quickly, becoming dense and diverse in just a few years.

Why Does the Tiny Forest Method Work So Well?

Here’s what makes it so powerful:

High-Density Planting Creates a Living Community

Instead of spacing trees far apart, Tiny forests plant 3–5 native species per square meter. This dense planting mimics how trees grow in wild forests — creating a living community where plants shelter and support one another. The close proximity also introduces just enough natural competition for light and space, which encourages strong, upward growth — while the shared canopy protects the soil, traps moisture, and supports the underground networks of roots and fungi.

Native Species Are Built for the Place

Each forest is made up of carefully selected species that occur naturally in the region. These trees are adapted to local conditions, soil, rainfall, and pests — so they naturally thrive, and because they’ve evolved together they form communities that support each other and host a great diversity of plants and animals.

Soil Is Restored and Supercharged

Before planting, the soil is enriched with organic compost and beneficial fungi (mycorrhizae). This recreates the living, breathing, sponge-like forest floor that helps trees access nutrients and water — and nurtures underground networks of roots and microbes.

Natural Layers Create a Mini-Ecosystem

Just like in an ancient forest, plants are chosen from different height layers: ground cover, shrubs, mid-level trees, and tall canopy species. These layers help:

- capture sunlight at every level,

- hold moisture in the soil,

- provide habitat diversity,

- and form a dense, self-sustaining ecosystem.

Rapid Growth + Low Maintenance

In the first 2–3 years, the forest needs regular care: weeding, watering, and protection. After that, it becomes self-sufficient. Trees planted this way grow up to 10 times faster than conventional methods — forming a full forest in just 20–30 years.

Tiny forests grow fast and thrive because they copy the way natural forests work — with shrubs, small trees, big trees, and a leafy canopy all working and growing together.

Tiny forests quickly became popular – they have lots of benefits:

Cooling and shade, even in cities and villages

Improved air quality and local biodiversity

Better water infiltration and storage in the soil

A boost to the small water cycle through evapotranspiration

Carbon storage

See our resources page for more information about how you can create mini forests.

Water is incredibly important

Without it, there is no life on our blue planet — and without it in our villages, gardens, fields, and cities, life becomes extremely difficult.

Restoring the small water cycle begins with reconnecting to water — noticing it again, appreciating it, and finding ways to keep it close.

The more water we hold, the more life it can support.

To close this story about climate and water, here’s a video with five inspiring projects from around the world. They show the enormous positive impact that water infiltration and tree planting can have — springs start flowing again, and once-dry rivers come back to life.

Enjoy!

Get involved in restoring the Small Water Cycle!

For more info go to the Resources page