What weakens the Water Cycle?

Loss of Trees and Forests

When we cut down trees, we lose their evaporative power — the steady release of moisture into the air through their “breathing.”

We also lose the shade that cools the land, the leaf litter that protects and feeds the soil, and the roots that help water infiltrate deep underground.

Forests are also a major source of condensation nuclei — especially the natural, biological ones that help clouds form even at warmer temperatures. Without them, rainfall becomes less likely.

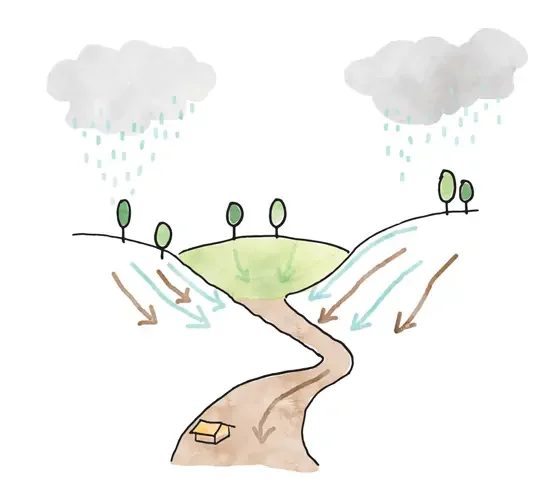

On slopes, the effects are even more dramatic. Where water once soaked slowly into forested ground, it now rushes off quickly — taking precious topsoil with it.

Trees and forest helps water infiltrate.

Loss of forest and trees leads to quick water loss and erosion.

Loss of Wetlands and Wet Grasslands

To make areas suitable for roads, agriculture, and building, wetlands and wetter grasslands — especially those along rivers and in low-lying fields — were drained. Rivers were also straightened and channelled, so instead of meandering and spilling into floodplains, they now carry water away much faster. This has taken away the rich mosaic of wet habitats — marshes, wet meadows, and the small side-pools and channels of winding rivers — that once stored water, supported wildlife, and fed the small water cycle. Ditches, canals, and flood control measures were all designed with the same goal: to remove water from the landscape as quickly as possible.

But these moist areas are key players in the water cycle. Covered with plants and rich soils, they release huge amounts of water vapor into the air — feeding clouds and helping local rain to form. They also store water like sponges, protecting nearby areas from both floods and drought.

When they disappear, we lose this natural moisture engine — and the land dries faster than before.

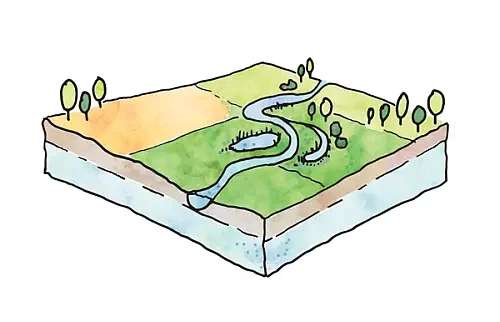

Natural meandering river with wetland and wet grasslands feeds the small water cycle.

When rivers and streams get straightened and wet areas drained, the landscape becomes drier, the water table becomes lower and less water is available for the small water cycle.

Modern Farming

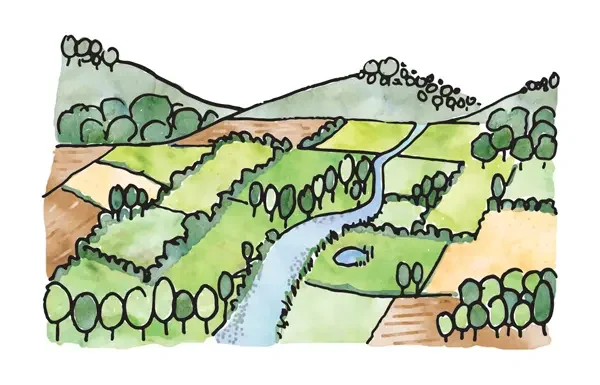

Before the arrival of tractors and combines, small-scale farming worked with the land’s shape. A patchwork of fields and meadows was surrounded by hedges, trees, and grassy boundaries — creating landscapes that slowed down rain and helped it soak into the soil.

With modern farming, these patchworks were replaced by vast monoculture fields. To make space for machines and maximize yield, hedgerows, trees, and field boundaries were removed.

What’s left is bare, exposed land — often without vegetation for much of the year. The soil heats up and dries out. Rain runs off instead of soaking in, and valuable topsoil is washed away. With no plants to shade the ground or release vapor, these large areas no longer feed the small water cycle.

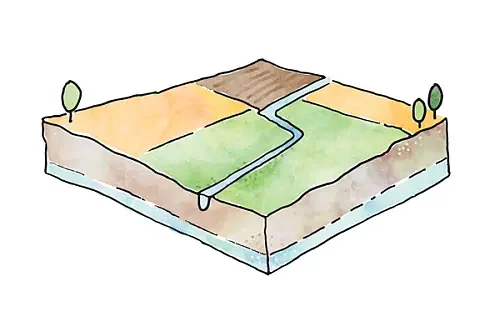

Small-scale traditional farming created a wetter landscape rich in vegetation; field boundaries, small woodlands, natural rivers and small ponds and wetlands. This feeds the small water cycle.

Modern agriculture led to bigger arable fields and loss of wetter areas, trees and bushes. Water is quickly lost from this landscape.

Urbanisation and Paved Surfaces

Over the past 120 years, many people moved from the countryside into cities. In these growing urban areas, the soil was covered over — replaced by buildings, roads, and parking lots. The result is vast areas of concrete and asphalt that are completely sealed off and impermeable.

Rain that falls on these surfaces turns into runoff. It’s seen as a problem — a flooding risk — and is quickly diverted into drainage channels and sewage systems designed to carry water away as fast as possible. Most of this water ends up in rivers that discharge it to the sea, removing it from the landscape at top speed.

None of it gets a chance to soak into the ground — to refill the soil, feed city trees, or power natural air conditioning through evaporation. Instead, the hard surfaces soak up heat and radiate it back, even at night — turning cities into heat islands that dry out faster and cool down slower than the land around them.

Undeveloped lots, trees and parks help water infiltrate in the city so trees and vegetation can thrive, cooling the city and making it a more pleasant place to live.

As urbanisation continues, more and more land is developed, cover of asphalt and concrete increases and trees and green spaces get lost. Less water infiltrates and instead quickly leaves through the sewage and drainage system.

The Disappearing Water: Why the Water Balance Matters

When we think of drought, we often imagine “not enough rain.”

But the real issue isn’t just how much rain falls — it’s how much stays.

In healthy landscapes, rainfall soaks into the ground, replenishing the soil, feeding springs, and returning to the air through plants. But in damaged landscapes — with bare soil, drained wetlands, and paved surfaces — most of that water is quickly lost.

It runs off into rivers and flows away to the sea.

It evaporates directly from hot, dry ground.

It can’t soak in, because the sponge is gone.

Over time, this creates a negative water balance:

More water is leaving the landscape each year than is entering or staying.

The result?

Lower groundwater. Drying springs. Fewer clouds. Longer droughts. Hotter summers.

And it doesn’t fix itself — unless we change the way we manage land and water.

From Dry to Drenched …

How a weakened Water Cycle Fuels Extreme Weather

Once the landscape loses its water-holding capacity, we don’t just get less rain — we get more extremes:

Longer Droughts

With less water in the ground and fewer plants releasing moisture, there’s less vapor in the air. That means fewer clouds, less local rain, and longer dry spells — even in places that used to get regular rainfall.

More Intense Downpours

When rain does come, the hardened, dry soil can’t absorb it. Instead of soaking in, it rushes over the surface, causing flash floods, erosion and loss of valuable topsoil and damage to homes and infrastructure. Nature’s sponge is gone — and the system can’t buffer or balance anymore.

Rising Storm Intensity

As landscapes heat up, they add more energy to the atmosphere. And when dry heat finally meets moist air, it can trigger sudden violent storms — lightning, hail, high winds, or even local tornado-like systems.

More Wildfires

Longer dry periods, less humidity, and degraded soils make it easier for fires to start and harder for them to stop. Wetlands and forests that once held moisture and slowed fire spread are now gone or dry.

How a landscape can shift into self-reinforcing, drying loop:

Less vegetation → less moisture → less rain

More heat → drier soil → less infiltration

More runoff → less groundwater → more drought

More drought → more fires → even less vegetation

But here’s the good news:

Because these cycles work both ways, we can flip them back — by restoring the water sponge and reactivating the small water cycle locally, right where we are. And it’s not that complicated…

See our resources page for more information about the New Water Paradigm and the Small Water Cycle.